How to Take Better Photographs

Many people think they'll improve their photography by buying a spiffy new

camera. The truth is, in photography, technique is much more important than

equipment. And taking good pictures is something anyone can do with any camera, if you practice enough and avoid some common mistakes.

Steps

Read the camera's manual, and learn what each control, switch, button, and menu item does. At the very least you should know how to turn the flash on, off, and auto, how to zoom in and out, and how to use the shutter button. Some cameras come with a printed beginners manual but also offer a larger manual for free on the manufacturer's website

Set the camera's resolution to take high quality photos at the highest resolution possible. Low-resolution images are more difficult to digitally alter later on; it also means that you can't crop as enthusiastically as you could with a higher-resolution version (and still end up with something printable). If you have a small memory card, get a bigger one; if you don't want to or can't afford to buy a new one, then use the "fine" quality setting, if your camera has one, with a smaller resolution.

Start off with setting your camera to one of its automatic modes, if you have a choice. Most useful is "Program" or "P" mode on digital SLRs. Ignore advice to the contrary which suggests that you operate your camera fully manually; the advances in the last fifty years in automatic focusing and metering have not happened for nothing. If your photos come out poorly focused or poorly exposed, then start operating certain functions manually.

Take your camera everywhere. When you have your camera with you all the time, you will start to see the world differently; you will look for and find opportunities to take great photographs. And, of course, you will end up taking more photographs; and the more you take, the better a photographer you will become.[1] Furthermore, if you're taking photographs of your friends and family, they will get used to you having your camera with you all the time. Thus, they will feel less awkward or intimidated when you get your camera out; this will lead to more natural-looking, less "posed" photographs. Also, remember to bring spare batteries or charge it if you are using a digital camera.

Get outside. Motivate yourself to get out and take photographs in natural light. Take several normal 'point and shoot' pictures to get a feel for the lighting at different times of the day and night. Go outside at all times of day, especially those times when anybody with any sense is sleeping, eating, or watching television; lighting at these times is often dramatic and unusual to many people precisely because they never get to see it!

Keep the lens clear of caps, thumbs, straps and other obstructions. It's basic, yes, but it can ruin a photograph completely. This is less of a problem with modern live-preview digital cameras, and even less of a problem with an SLR camera. But people still make these mistakes from time to time.

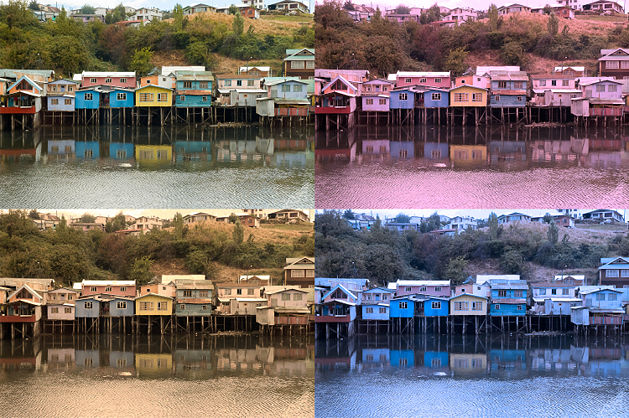

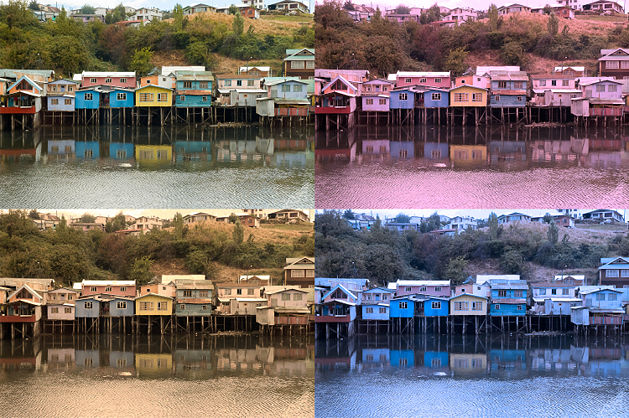

Set your white balance. Put simply, the human eye automatically compensates for different kinds of lighting; white looks white to us in almost any kind of lighting. A digital camera compensates for this by shifting the colors certain ways. For example, under tungsten (incandescent) lighting, it will shift the colours towards blue to compensate for the redness of this kind of lighting. The white balance is one of the most critical, and most underused, settings on modern cameras. Learn how to set it, and what the various settings mean. If you're not under artificial light, the "Shade" (or "Cloudy") setting is a good bet in most circumstances; it makes for very warm-looking colors. If it comes out too red, it's very easy to correct it in software later on. "Auto", the default for most cameras, sometimes does a good job, but also sometimes results in colours which are a little too cold.

Set a slower ISO speed, if circumstances permit. This is less of an issue with digital SLR cameras, but especially important for point-and-shoot digital cameras (which, usually, have tiny sensors which are more prone to noise). A slower ISO speed (lower number) makes for less noisy photographs; however, it forces you to use slower shutter speeds as well, which restricts your ability to photograph moving subjects, for example. For still subjects in good light (or still subjects in low light, too, if you're using a tripod and remote release), use the very slowest ISO speed that you have.

Set a slower ISO speed, if circumstances permit. This is less of an issue with digital SLR cameras, but especially important for point-and-shoot digital cameras (which, usually, have tiny sensors which are more prone to noise). A slower ISO speed (lower number) makes for less noisy photographs; however, it forces you to use slower shutter speeds as well, which restricts your ability to photograph moving subjects, for example. For still subjects in good light (or still subjects in low light, too, if you're using a tripod and remote release), use the very slowest ISO speed that you have.

Compose your shot thoughtfully. Frame the photo in your mind before framing it in the viewfinder. Consider the following rules, but especially the last one:

Compose your shot thoughtfully. Frame the photo in your mind before framing it in the viewfinder. Consider the following rules, but especially the last one:

- Use the Rule of Thirds, where the primary points of interest in your scene sits along "third" lines. Try not to let any horizon or other lines "cut the picture in half."[3]

- Get rid of distracting backgrounds and clutter. If this means you and your friend have to move a little so that a tree does not appear to be growing out of her head, then do so. If glare is coming off the windows of the house across the street, change your angle a bit to avoid it. If you're taking vacation photographs, take a moment to get your family to put down all the junk they may be carrying around with them and to remove backpacks or hip packs as well. Keep that mess well out of the frame of the picture, and you will end up with much nicer, less cluttered photos. If you can blur the background in a portrait, then do so. And so on.

Ignore the advice above. Regard the above as laws, which work much of the time but are always subject to judicious interpretation — and not as absolute rules. Too close an adherence to them will lead to boring photographs. For example, clutter and sharply focused backgrounds can add context, contrast and colour; perfect symmetry in a shot can be dramatic, and so on. Every rule can and should be broken for artistic effect, from time to time. This is how many stunning photographs are made.

Fill the frame with your subject. Don't be afraid to get closer to your subject. On the other hand, if you're using a digital camera with plenty of megapixels to spare, you can crop it later in software.

Try an interesting angle. Instead of shooting the object straight on, try looking down to the object, or crouching and looking up. Pick an angle that shows maximum color and minimum shadow. To make things appear longer or taller, a low angle can help. If you want a bold photo, it is best to be even with the object. You may also want to make the object look smaller or make it look like you're hovering over; to get the effect you should put the camera above the object. An uncommon angle makes for a more interesting shot.

Focus. Poor focusing is one of the most common ways that photographs are ruined. Use the automatic focus of your camera, if you have it; usually, this is done by half-pressing the shutter button. Use the "macro" mode of your camera for very close-up shots. Don't focus manually unless your auto-focus is having issues; as with metering, automatic focus usually does a far better job of focusing than you can.

Keep still. A lot of people are surprised at how blurry their pictures come out when going for a close-up, or taking the shot from a distance. To minimize blurring: If you're using a full-sized camera with a zoom lens, hold the camera body (finger on the shutter button) with one hand, and steady the lens by cupping your other hand under it. Keep your elbows close to your body, and use this position to brace yourself firmly. If your camera or lens has image stabilisation features, use them (this is called IS on Canon gear, and VR, for Vibration Reduction, on Nikon equipment).

Consider using a tripod. If your hands are naturally shaky, or if you're using very large (and slow) telephoto lenses, or if you're trying to take photographs in low light, or if you need to take several identical shots in a row (such as with HDR photography), or if you're taking panoramic photos, then using a tripod is probably a good idea. For very long exposures (more than a second or so), a cable release (for older film cameras) or a remote control is a good idea; you can use the self-timer feature of your camera if you don't have one of these.

Consider not using a tripod, especially if you don't already have one. A tripod infringes on your ability to move around, and to rapidly change the framing of your shot. It's also more weight to carry around, which is a disincentive to getting out and taking photographs in the first place. As a general rule,[5] you only need a tripod if your shutter speed is equal to or slower than the reciprocal of your focal length.[6] If you can avoid using a tripod by using faster ISO speeds (and, consequently, faster shutter speeds), or by using image stabilisation features of your camera, or by simply moving to somewhere with better lighting, then do that.

If you are in a situation where it would be nice to use a tripod, but you don't have a tripod at the time, try one or more of the following to reduce camera shake:

- Turn on image stabilization on your camera (only some digital cameras have this) or lens (generally only some expensive lenses have this).

- Zoom out (or substitute a wider lens) and get closer. This will de-magnify the effect of a small change in the direction of the camera, and generally increase your maximum aperture for a shorter exposure.

- Hold the camera at two points away from its center, such as the handle near the shutter button and the opposite corner, or toward the end of the lens. (Do not hold a delicate collapsible lens such as on a point-and-shoot, or obstruct something that the camera will try to move on its own such as a focusing ring, or obstruct the view from the front of the lens.) This will decrease the angle which the camera moves for a given distance your hands wobble.

- Squeeze the shutter slowly, steadily, and gently, and do not stop until momentarily after the picture has taken. Try putting your index finger over the top of the camera, and squeezing the shutter button with the second joint of the finger for a steadier motion (you're pushing on the top of the camera all along).

- Brace the camera against something (or your hand against something if you're concerned about scratching it), and/or brace your arms against your body or sit down and brace them against your knees.

- Prop the camera on something (perhaps its bag or its strap) and use the self-timer to avoid shake from pushing on the button if the thing it is propped on is soft. This often involves a small chance that the camera will fall over so check that it does not have far to fall, and generally avoid it with a very expensive camera or one with accessories such as a flash that could break or rip off parts of the camera. If you anticipate doing this much, you could bring along a beanbag, which would work well for it. Purpose-built "beanbags" are available, bags of dried beans are cheap and the contents can be eaten when they begin to wear through or get upgraded.

Relax when you push the shutter button. Also, try not to hold the camera up for too long; this will cause your hands and arms to be shakier. Practice bringing the camera up to your eye, focusing and metering, and taking the shot in one swift, smooth action.

Avoid red eye. Red-eye is caused when your eyes dilate in lower lighting. When your pupils are big, the flash actually lights up the blood vessels on the back wall of your eyeball, which is why it looks red. If you must use a flash in poor light, try to get the person to not look directly at the camera, or consider using a "bounce flash". Aiming your flash above the heads of your subjects, especially if the walls surrounding are light, will keep red-eye out. If you don't have a separate flash gun which is adjustable in this way, use the red-eye reduction feature of your camera if available — it flashes a couple of times before opening the shutter, which causes your subject's pupils to contract, thus minimizing red-eye. Better yet, don't take photographs which require a flash to be used; find somewhere with better lighting.

Use your flash judiciously, and don't use it when you don't have to. A flash in poor light can often cause ugly-looking reflections, or make the subject of your photo appear "washed out"; the latter is especially true of people photos. On the other hand, a flash is very useful for filling in shadows; to eliminate the "raccoon eye" effect in bright midday light, for example (if you have a flash sync speed[7] fast enough). If you can avoid using a flash by going outside, or steadying the camera (allowing you to use a slower shutter speed without blur), or setting a faster ISO speed (allowing faster shutter speeds), then do that.

If you do not intend the flash to be the primary light source in the picture, set it up to give correct exposure at an aperture a stop or so wider than that which is otherwise correct and which you actually use for the exposure (which depends on the ambient light intensity and the shutter speed, which cannot be above the flash-sync speed). This can be done by choosing a specific stop with a manual or thyristor flash, or by using "flash exposure compensation" with a fancy modern camera.

Go through your photos and look for the best ones. Look for what makes the best photos and continue using the methods that got the best shots. Don't be afraid to throw away or delete photos, either. Be brutal about it; if it doesn't strike you as a particularly pleasing shot, then ditch it. If you, like most people, are shooting on a digital camera, then it would not have cost you anything but your time. Before you delete them, remember you can learn a lot from your worst photos; discover why they don't look good, then don't do that.

Practice, practice, and practice. Take lots and lots of photos -- aim to fill your memory card, (or to use up as much film as you can afford to have developed, but don't mess with film until you can get decent pictures frequently with a simple digital camera: until then, you need to make many more glaring mistakes to learn from, and it's nice to make them for free and find out immediately, when you can figure out exactly what you did and why under the current circumstances it is wrong). The more pictures you take, the better you'll get, and the more you (and everyone) will like your pictures. Shoot from new or different angles, and find new subjects to take pictures of, and keep at it; you can make even the most boring, everyday thing look amazing if you're creative enough about photographing it. Get to know your camera's limitations, too; how well it performs in different kinds of lighting, how well auto-focus performs at various distances, how well it handles moving subjects, and so on.

Tips

- If the camera has a neck strap, use it! Hold the camera out so that that the neck strap is pulled as far as a can, this will help steady the camera. Furthermore, it'll also stop you from dropping the camera.

- When shooting photos of children, get down to their level! Pictures looking down at the top of a child's head are usually pretty lame. Stop being lazy and get on your knees.

- Keep a notebook handy and make notes about what worked well and what didn't. Review your notes often as you practice.

- To find an interesting angle at a tourist location, look where everybody else is taking their picture, and then go somewhere completely different. You don't want the same picture as everybody else.

- Install photo-editing software and learn how to use it. This will allow you to correct color balance, adjust lighting, crop your photos, and much more. Most cameras will come with software to make these basic adjustments. For more complicated operations, consider buyingPhotoshop, downloading and installing the free GIMP image editor, or using Paint.NET, a free light-weight photo editing program for Windows users.

- Get your photos off your memory card ASAP. Make backups; make several backups if you can. Every photographer has, or will, experience the heartbreak of losing a precious image/images unless he or she cultivates this habit. Back-up, back-up, back-up!

- Pick up a big-city newspaper or a copy of National Geographic and see how professional photojournalists tell stories in pictures. It's often worth poking around photo sites like Flickror deviantART for inspiration, too. Try Flickr's camera finder to see what people have done with the cheapest point-and-shoot cameras. Look at the Camera Data on deviantART. Just don't spend so much time getting inspired that it stops you from getting out there.

- Upload to Flickr or the Wikimedia Commons and maybe one day you will see your photos used on wikiHow!

- Your camera doesn't matter. Nearly any camera is capable of taking good photographs in the right conditions. Even a modern camera phone is good enough for many kinds of shots. [8]Learn your camera's limitations and work around them; don't buy new equipment until you know exactly what these limitations are, and are certain that they are hindering you.

- If you shoot digital it's better to underexpose the shot, as underexposure is easy to correct later on in software. Shadow detail can be recovered; blown highlights (the pure white areas in an overexposed photo) can never be recovered, as there is nothing there to recover. Film is the opposite; shadow detail tends to be poor compared to digital cameras, but blown highlights are rare even with massive overexposure.[9]